Miriam Pratt

In the early hours of 17th May 1913, a fire broke out in a house on Storey Way, Cambridge. As it raged, the flames spread to the adjoining building – a laboratory belonging to Cambridge University – causing further damage that left it in great need for repair. Once the fires were kept under control and eventually extinguished, the police moved in looking for evidence of its cause. They found a watch and remnants of a ladder that had been wrapped in paraffin-soaked cloth and set alight. It was arson, and the watch belonged to a woman from Norwich.

Miriam Pratt emerges into the history of Norwich and women almost as abruptly as she disappears. Her name appears in a February 1913 edition of the newspaper Suffragette, being thanked alongside 19 other women – including Dorothy Jewson, daughter of Jewson building merchants founder George Jewson – for participating in jumble sales and a stall at Norwich market in support of the Suffragette cause. It was Miriam’s actions later that year, though, that really made her name resonate across the world.

Aged 23 and working as a schoolteacher in Norwich, Miriam Pratt was lodging with her aunt and uncle on Turner Road. There is no record so far as we can find that explain how she exactly became involved in the cause for woman’s rights but presumably, like so many other people at the time, she recognised the bullshit inequality between genders at the time and was inspired by the possibility of another world being talked about by other women (and some men) around her.

Great though jumble sales and market stalls were for publicity it appears that by May, Pratt felt that more direct and radical action needed to be taken.

Olive Bartels was an organiser for the Cambridge branch of the Women’s Political and Social Union (WPSU). She is also instigator of the actions undertaken during the early hours of May 17th: choosing the targets, acquiring the paraffin, and making the appropriate arrangements for three women to set fire to two houses on Storey Way.

Whether Miriam was selected or self-elected is unknown. She left her lodgings on May 16th telling her uncle, William Ward, that she was heading to Cambridge to distribute leaflets concerning the Suffragette cause. Later that day she arrived in the university town and, presumably, gathered with her fellow plotters to engage with the night’s actions.

Olive Bartels selected two private properties on Storey Way that the group of three women – herself not included – would attack by means of wrapping ladders in paraffin-soaked cloth, setting fire to them, then making a run for it. The two properties chosen both appear to have been empty households, though information on the second is lacking as it was never successfully attacked. What we can gather about the first house, though, is it was a house under construction but close to completion being built for a Mrs Spencer that lived on Castle Street.

It was the burning of this house for which Miriam went to court.

Some time around 1am on the morning of May 17th, Miriam and two comrades made their way to Storey Way, to the house of Mrs Spencer. It is reported that the arsonists wanted access to the property though no reason is given in official reports: perhaps it was to ensure the house was empty, or perhaps it was simply to place the fire-starter inside the building. Either way, accessing the property would become one of two key moments in Miriam’s eventual prosecution.

To get inside, a decision was made to scrape away putty from the window frames and remove the windows. Miriam used a pair of scissors as a scraper and whilst doing somehow managed to injure her hand, leaving blood at the scene and a wound on her hand. Presumably the three women made it inside nonetheless and managed to set fire to the building. On their way out, perhaps rushed by the growing flames when climbing back through the window, Miriam’s watch must have got caught and ripped from her wrist without her realisation. It laid just outside the window, waiting to be discovered.

The flames grew, engulfing the house. Soon they roared fiercely enough to spread and began consuming the neighbouring laboratory, a property that belonged to Cambridge University and according to one source we found was involved with genetic research. By this point the attention of the local population would have been drawn, police called, the fire brigade brought out, and attempts made to bring the blaze under control.

Miriam and the two other women disappeared into the night, leaving the second building unattacked though apparently with the materials prepared and left at the scene. There are few details about the ensuing days but Miriam must have returned to Norwich, to her uncle and aunt’s house, and returned to her daily life – perhaps hyped and inspired by her actions, or perhaps anxious and worried about being discovered.

News broke fast about the blaze. Suffragettes claimed collective responsibility and the story made international news, no doubt due to the boldness of attacking an institution (however unintentionally) such as Cambridge University. Using the media to their advantage, the police reported that both blood and a gold watch had been found at the scene and that these likely belonged to the arsonists.

Unfortunately for Miriam, her uncle William was himself a policeman. After reading the reports, his suspicions were raised.

When he found the watch was missing he asked his niece if she had anything to do with the fire at Cambridge. She admitted being there with two others and said: “I did not set the house on fire.” There was a wound in her hand which, she said, had been caused by a pair of scissors which she used to break the glass.

William, horrified by Miriam’s participation in the arson, snitched on her.

Miriam was arrested within days. On the morning of 22nd May, she as taken into custody in Cambridge and bailed the same day by Dorothy Jewson and her brother Harry. Dorothy also set straight to work organising the defence fund for Miriam in preparation for her court date, which was set for October as Miriam left the police station and to be held at Cambridge Assizes.

The court hearing happened on the morning of 14th October 1913. Headed up by Justice Bray, it was the testimony of Miriam’s uncle William that landed her a jail sentence – though the law of the time was heavily weighted against Suffragette action and sought to make an example of them.

The judge declared that she and her kind would ruin England if allowed to vote.

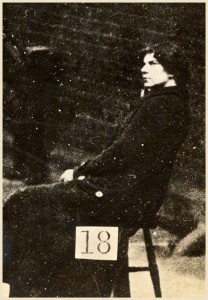

Despite her protestations that she was not herself the person that set the fire, Justice Bray sentenced Miriam to 18 months in prison for the charge of ‘incendiarism’. This was to be served at the infamous Holloway prison, London, a female jail where many Suffragettes served their terms. Miriam, following Suffragette tradition, immediately went on hunger strike.

In the days following, Suffragettes joined a service at Norwich Cathedral that was also being attended by Justice Bray and at some point during the service stood up, chanted “Lord, help and save Miriam Pratt and all those who are being tortured in prison for conscience sake,” then returned to their seats. Afterwards, they distributed leaflets outside the Cathedral containing Miriam’s defence speech.

It took just six days for Miriam to be released. Not because of appeals to authority, or even the pressure applied by her comrades on the outside, but because Miriam’s hunger strike had led her health to critical condition. She left Holloway on 20th October and according to one report we found went to stay with friends in Kensington. At this point the publicly known records of Miriam Pratt disappear. We do not know whether she recovered or whether she died from her ill health, nor whether she ever returned to Norwich.

What we do know is that she lived, if for a time only, in resistance and rebellion.

UPDATE 30/03/2018

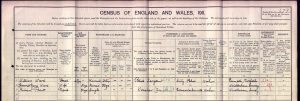

Below is an image of the 1911 National Census form showing Miriam Pratt living with her uncle William and aunt Harriet-Jane.

Miriam is listed as being a teaching assistant. William is marked as a police sergeant. Accompanying paperwork also lists Miriam’s birthplace as Windlesham, Surrey.

Tags: 1913, anarchism, anarchy, arson, cambridge, history, miriam pratt, norfolk, norwich, suffragettes, wpsu, writing